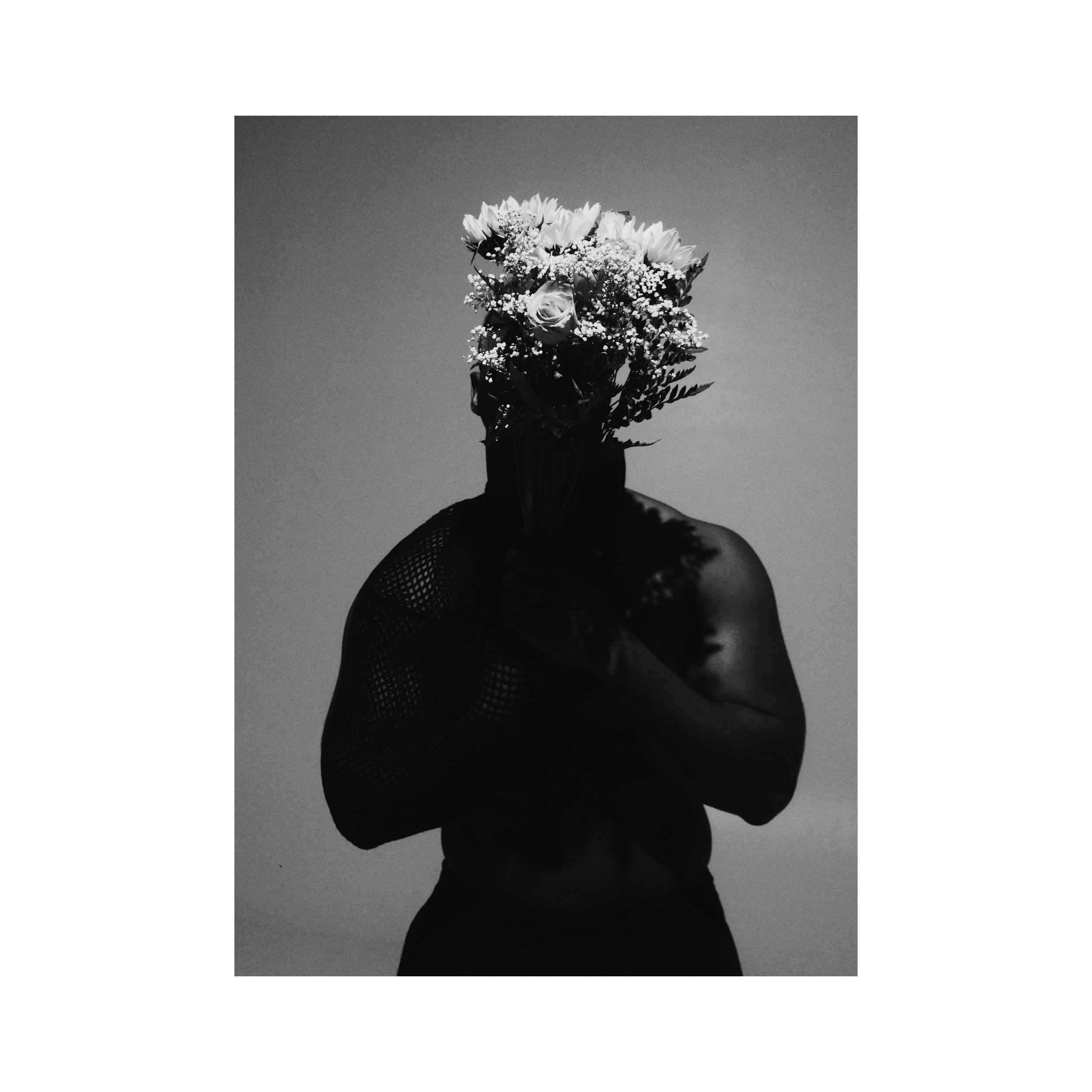

Art work by Isaac W. Joseph

Twoubadou: The Traveling Music of Haiti's Creolized Soul

In the early 1900s, as Haitian migrant workers carried their dreams and guitars between the sugar plantations of Cuba and the hills of home, they unknowingly birthed one of the Caribbean's most beautiful musical offspring. Twoubadou emerged from this constant movement—a music as portable as the lives of those who created it, requiring only acoustic guitars, maracas, a tanbou (drum), and voices seasoned by distance and desire.

The word itself carries the weight of centuries. From the medieval European troubadour comes this Haitian twoubadou—still a poet-musician, still singing of love's bitterness and humor, but now infused with the syncopated rhythms of Cuban guajiro and the lilting cadences of Haitian méringue. This wasn't mere musical borrowing; it was cultural alchemy at its finest.

As my friend Dr. Ibrahima Seck, Director of Research of the Whitney Plantation in Louisiana and recently honored with France's Ordre des Palmes Académiques, reminds us: "slavery is also a history of civilization"—in the sense that, in one of the darkest times of History, deported Africans were also enriching the culture of the Americas. Beyond the brutalities and economic exploitation, enslaved Africans and their descendants contributed to shaping and defining American culture and identity. Haiti stands as the paramount example of this cultural creolization, and twoubadou represents one of its most sublime results. These musician-poets carried with them the rhythmic memories of Africa, the harmonic structures of France, and the guitar stylings they'd learned in Cuban cane fields.

This genre represents so much of what's great about Haiti as an incubator for the arts, always bringing disparate cultures together to form wonderful new and uniquely West Indian expressions. In the hands of masters like Auguste de Pradines (known as Kandjo), twoubadou became the soundtrack of a people who had transformed their displacement into artistic triumph.

Tonight at Café Erzulie, as we listen to these traveling songs born of movement and memory, we celebrate not just a musical genre, but a testament to the creative resilience that turns migration into innovation, and cultural collision into transcendent art.

Written by Max Jean-Louis

September 25th, 2025 - Cafe Erzulie

Event by Mehïka Séphorah and Franck H Godefroy

Music by Rasin Okan and Lot Jan